1.Rapidly growing concern over Taiwan

Concern about a contingency related to Taiwan has grown rapidly since last year. This was triggered by the testimony of Admiral Philip Davidson, then commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, in response to a question by Republican Senator Dan Sullivan at a March 9, 2021 hearing of the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee. Admiral Davidson said the threat of an invasion of Taiwan “is manifest during this decade, in fact in the next six years,” and added that it is a preliminary step in China’s ambition to wrest the leadership of the international order from the U.S. by 2050[1]. Earlier this year, at a press conference during his visit to Japan, U.S. President Joe Biden made headlines when a reporter asked him, “Are you willing to get involved militarily to defend Taiwan?” and he responded with a clear, “Yes[2].”

On the other hand, there are more circumspect views about the likelihood of a military invasion of Taiwan. Many experts on China in Japan believe that a full-scale military invasion of Taiwan is unlikely for internal political reasons[3]. Others believe that Davidson’s testimony was a ploy to obtain a larger military budget[4].

However, since Russia's military invasion of Ukraine in February of this year, the Japanese public has widely come to realize that even today in the 21st century a major power may use aggressive military force to change the status quo. In a poll conducted by the Nikkei Shimbun, 90% of respondents said that Japan should prepare for a Taiwan contingency[5]. Since last year, think tanks in both Japan and the U.S. have also conducted numerous simulations of a possible Taiwan contingency[6]. Such simulations assume, in light of the situation in Ukraine, not only kinetic combat but also attacks in cyberspace from the gray zone phase.

As a mental exercise, this paper will consider what could happen in the event of a Taiwan contingency based on the lessons learned from the war in Ukraine and China's future warfare plans.

2.Hybrid warfare in Ukraine

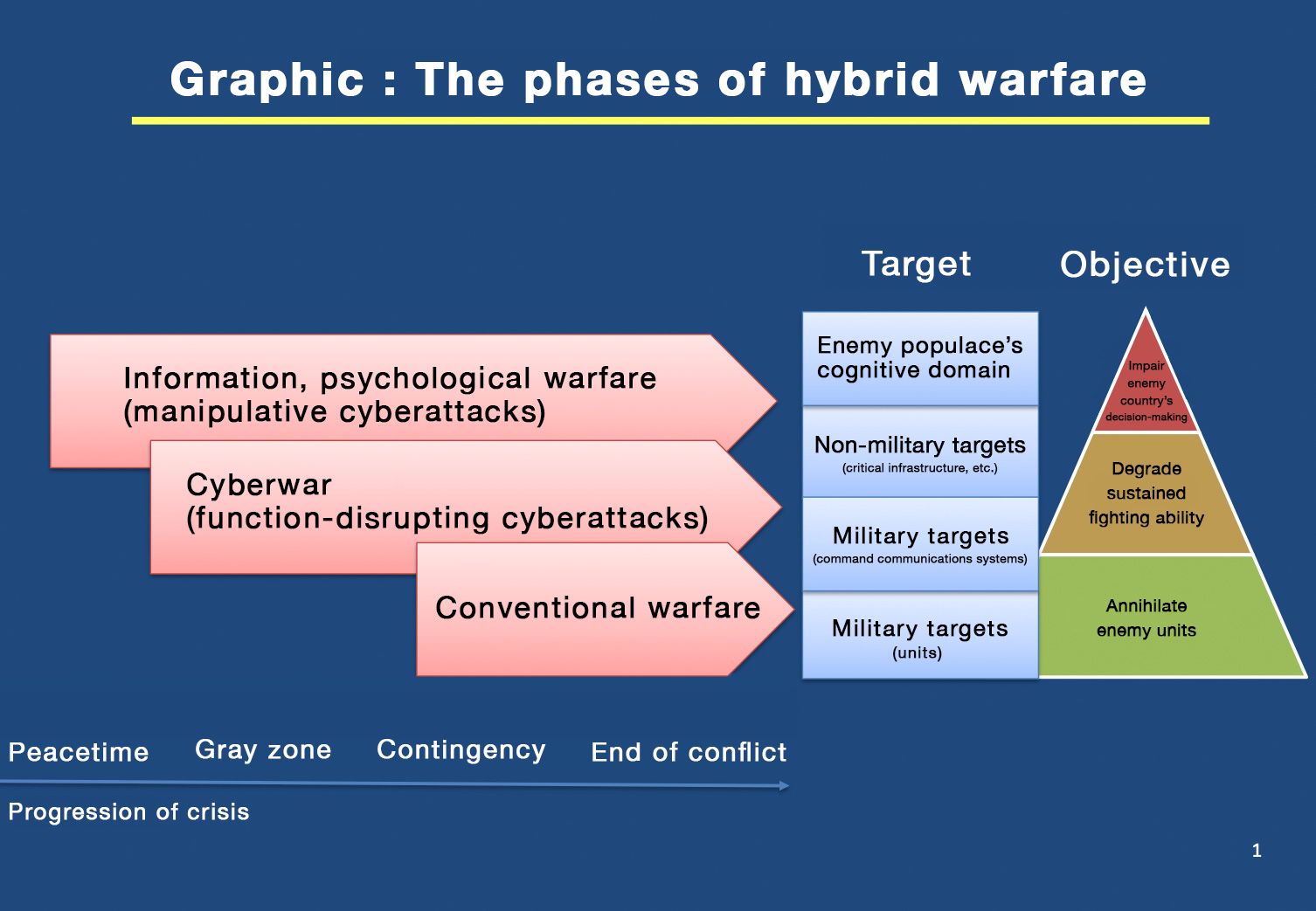

In the war in Ukraine, Russia is conducting full-scale “hybrid warfare[7].” Russia’s hybrid warfare is conducted in three stages, as shown in figure 1. The first stage is information and psychological warfare, which takes place in peacetime, long before the fighting begins. Information warfare is conducted through manipulative cyberattacks[8] that disseminate disinformation to divide society and discredit government agencies. In the case of the recent Ukraine conflict, since the collapse of the pro-Russia Yanukovych government, a false discourse had been spread by Russia that the Ukrainian government was filled with neo-Nazis and oppressing the Russian population. This was done to discredit the pro-Europe Ukrainian government.

Furthermore, just prior to the outbreak of the conflict Russia continued to issue false information indicating it would not invade Ukraine. This included statements such as, “Russian military units have withdrawn from Ukraine's borders” and “the Russian government will continue its diplomatic efforts.” Additionally, after the military invasion, to demoralize the Ukrainian people Russia spread the false news that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy had fled Kyiv[9], and in mid-March a fake video using deepfake technology (AI-based human image and video synthesis technology) showed Zelenskyy calling on the Ukrainian people to surrender. The video spread on Twitter and YouTube[10].

Russia is also conducting extensive information warfare against the international community[11]. The most prominent example is the notion that the cause of the current Ukraine war is NATO’s eastward expansion. Such discourse that justifies Russia's actions is becoming influential outside of the West.

In the second phase of cyber warfare, three waves of cyberattacks were launched against Ukraine before any actual fighting occurred[12]. At this stage, the objectives were to paralyze critical infrastructure in Ukraine, such as the power grid and telecommunications network, to disrupt government functions, and to degrade the opponent's will to conduct sustained combat. The first wave was launched in mid-January under the guise of ransomware. A Ukrainian government agency's website was defaced to display the message “Fear the worst.” The second wave occurred on February 15. DDoS attacks were launched against Ukraine's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Defence, state-owned commercial bank PrivatBank and state-owned savings bank OschadBank to disrupt their communications. This made mobile banking unavailable and cash withdrawals from ATMs impossible. The third wave was detected on February 23, just before the military invasion. Microsoft discovered the malware “Hermetic Wiper,” which was sent to destroy public and private computers in Ukraine, including financial, defense, aviation, and telecommunications systems. The third wave did not cause significant damage because countermeasures had been taken just prior and critical infrastructure had been shut down, meaning the damage was localized.

When the military invasion began on February 24, cyberattacks targeted military command and communications systems in an attempt to disrupt and paralyze them. The attack was accompanied by a combination of cyber and electromagnetic sabotage of Ukraine's internet infrastructure and the Ka-band communications satellites used by the Ukrainian military[13]. There was also localized electromagnetic interference with GPS.

Thus, the fighting in Ukraine has involved not only with conventional equipment such as manned combat aircraft, tanks and artillery, but also in new domains such as space, cyber, and the electromagnetic spectrum. Whether one can dominate a hybrid war has become a decisive factor on the battlefield.

3.The PLA and brain control warfare: the fight for the cognitive domain

Hybrid warfare and information warfare are not unique to Russia. Since Sun Tzu, China too has employed the strategy of “subduing the enemy without fighting,” and in a contingency, the strategy of the People's Liberation Army (PLA) has been to win before fighting militarily through psychological warfare, public opinion warfare, and legal warfare. The political work regulations of the PLA[14], revised in 2003 and 2010, state that the army "will conduct public opinion, psychological and legal warfare, and deploy degradation work, anti-psychological and anti-countermeasure work, military justice, and legal service work[15].”

Since 2013, China has taken this a step further, launching the concept of "brain control" to win the battle in the cognitive space. This "brain control" consists of the concepts of "cognitive suppression," which weakens or eliminates the enemy's ability to understand a situation; "cognitive formation," which uses false information to erode the enemy's will and lead to erroneous judgments; and "cognitive domination," which tampers with the enemy's decision-making mechanisms[16]. As a contingency approaches, China will not hesitate to conduct brain control warfare.

China aims for victory in the "informationization of war" as a military strategy and reorganized the PLA in December 2015, integrating units in charge of information warfare, cyber warfare, space warfare, and electronic warfare to form the Strategic Support Unit. The unit has 175,000 personnel, 30,000 of whom are thought to be dedicated to cyberattacks[17]. In addition, it is estimated that tens to hundreds of thousands of cyber militias can be mobilized.

4.Hybrid warfare in a Taiwan contingency

What kind of hybrid warfare is expected in a Taiwan contingency?

The first phase of hybrid warfare may have already begun. Since 2016, Taiwan has suffered manipulative cyberattacks targeting the democratic process, including the mass dissemination of opinions in support of pro-China candidates in presidential, national, and local elections, as well as mass postings attacking anti-China candidates on social media[18]. These cyberattacks were aimed at ousting Democratic Progressive Party candidates, who seek more distance from mainland China, and support Kuomintang candidates, who want stronger ties with Beijing. In response to this interference, Taiwan in January 2021 enacted the Anti-Infiltration Law, which bans election campaigning and lobbying by foreign hostile forces, and, with China’s information warfare in mind, prohibits the spread of false information related to the election.

As described above, attempts have been made for many years to unify Taiwan, predominantly by the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front Work Department, but in 2021 the phrase “develop Taiwan’s patriotic unification capacity” appeared in the United Front Work Department’s regulations[19]. If the United Work Front Department’s operations against Taiwan are unsuccessful and a peaceful unification appears out of reach, Beijing will become more likely to decide upon a “special military operation” to unify Taiwan using military force. One can easily imagine a hybrid war in Taiwan, similar to that taking place in Ukraine, as a contingency nears.

In the first stage of information and psychological warfare, China will attempt to discredit the Taiwanese government and divide Taiwanese society by spreading disinformation, including fake news, and it will use information warfare to suggest to Japan, the U.S. and the international community that it is holding economic relations hostage to deter intervention by foreign powers. When an armed attack becomes imminent, China will likely spread the narrative that "the Taiwanese government, spurred by U.S. and Japanese intrigue, is planning to declare independence from China," and that China has no choice but to use force to justify the use of force domestically.

On top of that, to avoid falling into a rut as Russia has in Ukraine, the second stage of cyber warfare will be a more intense attack to fully block domestic and international communications with Taiwan, disrupt internal communications and paralyze Taiwanese government functions and critical infrastructure. Most communication between Taiwan and the rest of the region is carried out via undersea cables, which land at four locations: Pali, Tamsui, and Toucheng near Taipei, and Fangshan near Kaohsiung. These undersea cables and the satellite communications operated by Taiwan's Chunghwa Telecom would be the first targets to come under electromagnetic, cyber and physical attack.

Japan would also be involved in the hybrid war that would come with a Taiwan contingency. To deter U.S. support for Taiwan, China may target critical infrastructure in the U.S. and Japan, such as electric power, telecommunications and cloud centers, with denial-of-service cyberattacks to cause domestic disruption. Japan's preparedness in the cyber domain is lagging, but in the event of a contingency in Taiwan the development of a system for the cyber domain, which is critical for Japan’s national security, will be a top priority that must be addressed at all costs.

(2022/09/07)

Notes

- 1 Committee on Armed Services United States Senate, Hearing to receive Testimony on United States Indo-Pacific Command in review of the Defense Authorization Request for Fiscal Year 2022 and the Future Years defense Program, March 9, 2021.

- 2 U.S. White House, “Remarks by President Biden and Prime Minister Kishida Fumio of Japan in Joint Press Conference,” May 23, 2022.

- 3 See, for example, the following interview with Professors Shin Kawashima and Yasuhiro Matsuda of the University of Tokyo.

(Kawashima) Eisuke Mori, “Two reasons why a Taiwan contingency will not happen in the near future,” Nikkei Business, June 21, 2021.(Japanese)

(Matsuda) Eisuke Mori, “Armed unification with Taiwan unlikely in next 10 years,” Nikkei Business, August 24, 2021. (Japanese) - 4 Kazuhisa Ogawa, “Do not be fooled by superficial info on a Taiwan contingency,” Jiji Press, November 7, 2021.(Japanese)

- 5 “On Taiwan contingency: ‘over 90% prepare,’ ‘50% stay in current legal framework,’ ‘40% change laws;’ 60% favor ‘counterattack capability,’” Nikkei Shimbun, May 30, 2022.(Japanese)

- 6 For example, Sasakawa Peace Foundation, “FY2020 TTX (Table Top Exercise) Report: Challenges for U.S.-Japan Joint Response to Taiwan Crisis Triggered by Cyber Attack,” April 2022.

Japan Forum for Strategic Studies, “Summary of Results of the First Policy Simulation: In-depth Review: How Japan Should Deter and Cope in a Taiwan Crisis,” August 2021.

Stacie Pettyjohn, Becca Wasser, and Chris Dougherty, “Dangerous Straits: Wargaming a Future Conflict over Taiwan,” CNAS, June 15, 2022. - 7 For more on hybrid warfare, see Jun Osawa, “Cyber Space, the Main Battleground: ‘Exclusive Defense’ Cannot Protect Japan,” Wedge, December 2021, pp. 24-27.

- 8 For more on information manipulation through cyberattacks, see Jun Osawa, Chuokoron-Shinsha, “How to Protect Japan from the Threat of Cyber Information Manipulation,” Chuokoron, April 2022, pp. 154-161.

- 9 For example, Russian news wire Tass on February 26 carried this story: “Zelensky hastily fled Kiev, Russian State Duma Speaker claims,” Tass, February 26, 2022.

- 10 Jane Wakefield, “Deepfake presidents used in Russia-Ukraine war,” BBC News, March 18, 2022.

- 11 European Commission, “Disinformation About Russia's invasion of Ukraine - Debunking Seven Myths spread by Russia,” January 24, 2022.

- 12 For more on the cyberattacks against Ukraine, see: “Special Report: Ukraine An overview of Russia’s cyberattack activity in Ukraine,” Microsoft, April 27, 2022.

- 13 On hybrid warfare associated with military invasions, Jun Osawa, "New Developments for Future Warfare," Seiron, The Sankei Shimbun, August 2022, pp. 84-91.

- 14 Article 14, Item 18 of “Regulations on Political Work of the Chinese People's Liberation Army.”

- 15 Strategic Research Group, Japan Air Self-Defense Force Staff College, "China's Definition of Three Battles and Other Examples of Three Battles on Air Power," Japan Air Self-Defense Force Staff College, ed., Air Power Research, no. 2, pp. 114-124. (Japanese)

- 16 Masafumi Iida, "China's Goals for Warfare in the Cognitive Domain," NDIS Commentary, National Institute for Defense Studies, No. 177, June 29, 2021. (Japanese)

- 17 Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan (annual white paper, 2021 edition), p. 140. (Japanese)

- 18 See Sasakawa Peace Foundation, Security Project Group, "'Ensuring Japan's Cyber Security' Project Policy Proposal: "Be Prepared for Foreign Disinformation! - Threat of Information Manipulation in Cyberspace -," February 2022, pp. 12-13. (Japanese)

- 19 Madoka Fukuda, “The Xi Jinping Administration's Operations against Taiwan: Its Current Status and Prospects,” Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association, Koryu, no. 961, April 2021. (Japanese)